콜라보레이티브 펀드에 Morgan Housel가 작성한 짧지만 강력한 글이 있어서,

적당히 이해가 갈 정도로 번역했다.

------

A list of ideas, in no particular order and from different fields, that help explain how the world works:

아래에 순서 없이 나열된, 각기 다른 분야에서 나온 이 아이디어들은, 세상이 어떻게 돌아가는 지 이해하는데 도움이 된다.

Depressive Realism: Depressed people have a more accurate view of the world because they’re more realistic about how risky and fragile life is. The opposite of “blissfully unaware.”

우울한 현실주의: 우울한 사람들은 세상을 더 정확하게 볼 수 있다. 왜냐하면 그들은 삶이 얼마나 위험하고 연약한지에 대해 더 현실적이기 때문이다. “모르는 게 약” 이라는 표현의 반대라 할 수 있다.

Skill Compensation: People who are exceptionally good at one thing tend to be exceptionally poor at another.

스킬 등가교환: 어떤 분야에서 놀랍도록 뛰어난 사람은 다른 분야에서는 놀랍도록 무능한 경향이 있다.

Curse of Knowledge: The inability to communicate your ideas because you wrongly assume others have the necessary background to understand what you’re talking about.

지식의 저주: 당신의 아이디어가 효과적으로 전달되지 않은 이유는 당신이 다른 사람들이 그에 필요한 배경 지식을 가지고 있다고 착각하고 있기 때문이다.

Base Rates: The success rate of everyone who’s done what you’re about to try.

확률(기저율): 당신이 시도하려는 것과 비슷한 것을 한 사람들의 성공률.

Base-Rate Neglect: Assuming the success rate of everyone who’s done what you’re about to try doesn’t apply to you, caused by overestimating the extent to which you do things differently than everyone else.

확률 무시: 당신이 시도하려는 것과 비슷한 것을 한 사람들의 성공률이 당신에게는 적용되지 않는다고 가정하는 것은, 당신이 노력한 정도가 다른 사람들보다 낫다고 과대평가하기 때문이다.

Compassion Fade: People have more compassion for small groups of victims than larger groups, because the smaller the group the easier it is to identify individual victims.

동정심 희석: 사람들은 대규모보다 소규모의 희생자들에게 더 많은 동정심을 가진다. 왜냐하면 소규모일수록 그 희생자 개개인을 알아보기 더 쉽기 때문이다.

System Justification Theory: Inefficient systems will be defended and maintained if they serve the needs of people who benefit from them – individual incentives can sustain systemic stupidity.

시스템 정당화 이론: 어떤 시스템이 비효율적이라 할지라도 그 안에서 이득을 보는 구성원들이 있다면 그 시스템은 종종 보호받거나 유지되곤 한다. 이러한 개별적인 인센티브가 시스템적인 어리석음을 계속되게 만들 수 있다.

Three Men Make a Tiger: People will believe anything if enough people tell them it’s true. It comes from a Chinese proverb that if one person tells you there’s a tiger roaming around your neighborhood, you can assume they’re lying. If two people tell you, you begin to wonder. If three say it’s true, you’re convinced there’s a tiger in your neighborhood and you panic.

세 사람이 우기면 없는 호랑이도 만든다: 사람들은 충분히 많은 다른 사람들이 무언가를 사실이라고 주장하면 그것을 믿게 된다. 이것은 중국 속담에서 유래된 것인데, 만약 한 사람이 호랑이가 주변에 돌아다닌다고 말하면 그것을 믿지 않지만, 두 사람이 그렇게 말하면 긴가민가하게 된다. 마침내 세 사람이 그렇게 주장하면 진짜 호랑이가 있는 줄 알고 패닉에 빠지고 만다.

Buridan’s Ass: A thirsty donkey is placed exactly midway between two pails of water. It dies because it can’t make a rational decision about which one to choose. A form of decision paralysis.

뷔리당의 당나귀: 목마른 당나귀가 정확히 두 물통 사이에 위치해 있다. 어느 쪽 물을 먹어야 하는지 이성적인 결정을 내릴 수 없는 당나귀는 결국 목말라서 죽게 된다. 일종의 의사결정 마비(우유부단한 사람을 비꼬는)라고 할 수 있다.

Pareto Principle: The majority of outcomes are driven by a minority of events.

파레토 법칙: 소수의 사건이 대부분의 결과를 만든다(상위 20%가 전체 생산의 80%를 해낸다).

Sturgeon’s Law: “90% of everything is crap.” The obvious inverse of the Pareto Principle, but hard to accept in practice.

스터전의 법칙: “모든 것의 90%는 쓰레기다.” 파레토 법칙에 명백히 반대되는 말이지만, 현실에서 받아들이기는 쉽지 않다.

Cumulative advantage: Social status snowballs in either direction because people like associating with successful people, so doors are opened for them, and avoid associating with unsuccessful people, for whom doors are closed.

누적되는 이익: 사회적 지위는 어느 쪽으로든 눈덩이처럼 커진다. 왜냐하면 사람들은 성공한 사람들과 어울리는 것을 좋아하기 때문에, 그들에겐 문이 열어놓지만, 그렇지 못한 사람들에겐 문을 닫아 놓기 때문이다.

Impostor Syndrome: Fear of being exposed as less talented than people think you are, often because talent is owed to cumulative advantage rather than actual effort or skill.

가면 증후군: 자신의 실제 재능이 사람들이 생각하는 것보다 못해 보일까봐 두려움을 느끼는 것. 재능이란 것은 실제 노력이나 능력보다는 오랜 기간 누적된 행동의 차이에서 오기 때문이다. (Ex: 10년간 그림을 그린 화가가 처음 그림을 그리는 사람들의 미숙함을 이해하지 못하는 경우)

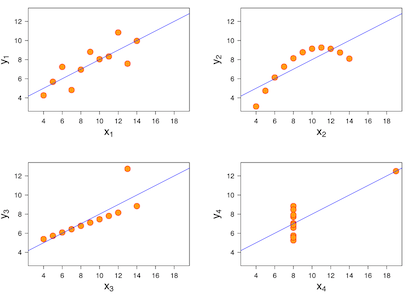

Anscombe’s Quartet: Four sets of numbers that look identical on paper (mean average, variance, correlation, etc.) but look completely different when graphed. Describes a situation where exact calculations don’t offer a good representation of how the world works.

앤스컴 콰르텟: 평균, 분산, 상관관계와 같은 숫자들은 종이에 써 있을 때는 동일한 것으로 보인다. 하지만 그래프로 표시하면 완전히 다르게 나타난다. 이처럼 세상이 어떻게 돌아가는 지를 정확한 계산만으로는 잘 표현할 수 없는 상황에서 쓰이는 용어이다.

Ringelmann Effect: Members of a group become lazier as the size of their group increases. Based on the assumption that “someone else is probably taking care of that.”

링겔만 효과: 그룹의 구성원들은 그 그룹이 커질수록 게을러지는 경향이 있다. “누군가는 해주겠지.” 라는 생각을 하고 있기 때문이다.

Semmelweis Reflex: Automatically rejecting evidence that contradicts your tribe’s established norms. Named after a Hungarian doctor who discovered that patients treated by doctors who wash their hands suffer fewer infections, but struggled to convince other doctors that his finding was true.

Semmelweis 반사: 당신이 속한 집단의 규범에 모순되는 증거는 자동적으로 거부하게 되는 현상. 손을 씻는 의사에게 치료받는 환자들이 덜 감염된다는 걸 발견한 헝가리 의사의 이름을 따와서 만들어졌다. 이 의사는 이러한 사실을 다른 의사들에게 납득시키는데 무진장 애를 썼다.

False-Consensus Effect: Overestimating how widely held your own beliefs are, caused by the difficulty of imagining the experiences of other people.

잘못된 합의 효과: 사람들은 타인의 경험을 상상하는 것이 어렵기 때문에 자신의 신념이 널리 받아들여진다고 과대평가한다.

Boomerang Effect: Trying to persuade someone to do one thing can make them more likely to do the opposite, because the act of persuasion can feel like someone stealing your freedom and doing the opposite makes you feel like you’re taking your freedom back.

부메랑 효과: 누군가에게 어떤 일을 하라고 설득하려고 하면 오히려 그 반대의 일을 할 가능성이 커질 수 있는데, 그것은 그 누군가가 당신의 설득에 자유를 뺏긴 느낌을 받아 그에 반대되는 행위를 함으로써 심적 안정을 얻으려 하기 때문이다.

Chronological Snobbery: “The assumption that whatever has gone out of date is on that account discredited. You must find why it went out of date. Was it ever refuted (and if so by whom, where, and how conclusively) or did it merely die away as fashions do? If the latter, this tells us nothing about its truth or falsehood. From seeing this, one passes to the realization that our own age is also ‘a period,’ and certainly has, like all periods, its own characteristic illusions.” – C.S. Lewis

연대기적 속물근성: “어떤 무언가가 시대에 뒤떨어졌다고 가정한다면 왜 그것이 시대에 뒤떨어진 것인지 말할 수 있어야 합니다. 그것이 구체적인 다른 누군가, 무엇에 의해서 반박돼서 그렇게 된 건지 아니면 그냥 유행처럼 시간이 지남에 따라 자연스레 사라진 건지를 말입니다. 만약 후자의 경우라면, 그것이 잘못된 건지 아닌지는 알 수는 없는 겁니다. 이러한 점을 봤을 때, 우리가 살고 있는 시대 역시 다른 시대와 다르지 않으며, 다른 시대에서 그랬듯이, 우리도 우리 시대가 특별하다는 환상을 품고 있다는 것을 깨달을 수 있습니다.” - C.S. 루이스

Planck’s Principle: “A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.”

플랑크의 원리: 새로운 과학적인 진리는 그것에 반대하는 사람들을 설득하고 그들을 깨우침으로써 받아들여지는 것이 아니라, 그들이 결국 죽어 없어지고 그 진리에 익숙한 새로운 세대가 자라남으로써 받아들여지게 된다.

McNamara Fallacy: A belief that rational decisions can be made with quantitative measures alone, when in fact the things you can’t measure are often the most consequential. Named after Defense Secretary McNamara, who tried to quantify every aspect of the Vietnam War.

맥나마라의 오류: 합리적인 판단은 양적인 수치만 보고도 내릴 수 있다는 믿음. 하지만 현실에선 정량화 할 수 없는 것들이 가장 중요한 경우가 많다. 베트남 전쟁의 모든 측면을 양적으로만 판단했던 미국의 국방장관 맥나마라의 이름을 따서 만들어진 오류이다.

Courtesy Bias: Giving opinions that are likely to offend people the least, rather than what you actually believe.

예의상 발언: 사람들에게 자신이 믿는 것을 말하기보단 그들이 덜 기분 나빠할 이야기를 해주는 것.

Berkson’s Paradox: Strong correlations can fall apart when combined with a larger population. Among hospital patients, motorcycle crash victims wearing helmets are more likely to be seriously injured than those not wearing helmets. But that’s because most crash victims saved by helmets did not need to become hospital patients, and those without helmets are more likely to die before becoming a hospital patient.

버크슨의 역설: 서로 강한 상관관계가 있어 보이는 사건도 크게 봤을 때는 잘못된 경우가 있다. 예를 들어 병원에서, 헬멧을 쓴 오토바이 사고 피해자가 안 쓴 피해자보다 더 심하게 다치는 경향이 나타날 수 있다. 하지만 그것은 헬멧을 쓴 피해자는 애초에 병원에 올 만큼 다치지 않았고, 헬멧을 안 쓴 피해자는 오기 전에 이미 죽은 경우가 있다는 사실을 간과한 해석이다.

Group Attribution Error: Incorrectly assuming that the views of a group member reflect those of the whole group.

그룹 속성 오류: 일부 그룹의 견해가 전체 그룹의 견해를 대변한다고 잘못 가정하는 것.

Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon: Noticing an idea everywhere you look as soon as it’s brought to your attention in a way that makes you overestimate its prevalence.

바이더-마인호프 현상: 어떤 것에 관심을 가지기 전까진 몰랐다가 관심을 가지게 된 이후 갑자기 여기저기서 그것과 관계된 것이 눈에 띄는 현상. 이 현상이 발생하면 실제보다 그것의 중요성을 더 과대평가하게 될 수 있다.

Ludic Fallacy: Falsely associated simulations with real life. Nassim Taleb: “Organized competitive fighting trains the athlete to focus on the game and, in order not to dissipate his concentration, to ignore the possibility of what is not specifically allowed by the rules, such as kicks to the groin, a surprise knife, et cetera. So those who win the gold medal might be precisely those who will be most vulnerable in real life.”

루딕 오류: 시뮬레이션의 논리를 현실에서도 적용하려다 발생하는 오류. “올림픽 경기에서 체계적이고 경쟁적인 싸움 훈련 방식은 선수들로 하여금 집중력 유지를 위해, 규칙에서 허용되지 않는 것들(사타구니 차기, 기습적인 나이프 공격 등)은 완전히 무시하도록 가르칩니다. 하지만 그렇게 금메달을 딴 선수들은 현실에서도 그런 공격을 무시할 수 있기 때문에 오히려 가장 위험한 상황에 처할 수도 있습니다.” – 나심 탈레브

Normalcy Bias: Underestimating the odds of disaster because it’s comforting to assume things will keep functioning the way they’ve always functioned.

정상화 편향: 사람들이 재난이 발생할 확률을 과소평가하는 이유는 어떤 일이 항상 제 기능을 하며 정상 작동할 것이라고 가정하는 것이 몹시 편하기 때문이다.

Actor-Observer Asymmetry: We judge others based solely on their actions, but when judging ourselves we have an internal dialogue that justifies our mistakes and bad decisions.

행위자-관찰자 불균형: 사람들은 다른 사람들을 평가할 때 그들의 행동을 기반으로 평가한다. 하지만 자기 스스로를 평가할 때는 자신의 잘못된 행동과 결정을 정당화하는 내적 대화를 나눈다.

The 90-9-1 Rule: In social media networks, 90% of users just read content, 9% of users contribute a little content, and 1% of users contribute almost all the content. Gives a false impression of what ideas are popular or “average.”

90-9-1 규칙: 소셜 미디어 네트워크에 있어서, 90%의 유저들은 그저 컨텐츠를 읽기만 하고, 9%는 컨텐츠에 아주 작은 기여만 하며, 1%의 사람들 만이 대부분의 컨텐츠를 작성한다. 이는 어떤 아이디어가 인기있는지 혹은 “평균”적인 것인지에 대해 잘못된 인상을 심어준다.

Texas Sharpshooter Fallacy: Goals set retroactively after an activity, like shooting a blank wall and then drawing a bullseye around the holes you left, or picking a benchmark after you’ve invested.

텍사스 명사수의 오류: 빈 벽에다 총을 쏜 뒤 많이 맞은 곳에 과녁을 그려 넣는 행위처럼 활동 후에 목표를 설정하는 것을 말한다. 먼저 어느 기업에 투자한 후에 벤치마크 할 기업을 고르는 것 역시도 포함된다.

Fredkin’s Paradox: Confronted with two equally good options, you struggle to decide, even though your decision doesn’t matter because both options are equally good. The more equal the options, the harder the decision.

프레드킨의 역설: 똑같이 좋은 두 가지 옵션을 선택할 때가 되면, 비록 그 결정에 차이가 없더라도 사람들은 의사결정에 애를 먹는다. 이는 두 옵션의 차이가 적을수록 더 심해진다.

Poisoning the Well: Presenting irrelevant adverse information about someone in a way that makes everything else that person says seem untrustworthy. “Before you hear my opponent’s healthcare plan, let me remind you that he got a DUI in college.”

우물에 독 풀기: 어떤 사람이 말하는 모든 것을 믿을 수 없게 만들기 위해 관계는 없지만 그에 대한 부정적인 정보를 살포하는 방법. “여러분이 저 사람의 건강보험 계획에 대해 듣기 전에, 제가 한 마디 하겠습니다. 저 사람은 대학 때 음주 운전을 한 적이 있습니다.”

Golem Effect: Performance declines when supervisors/teachers have low expectations of your abilities.

골렘 효과: 당신의 감독관/교사가 당신의 능력에 낮은 기대치를 갖고 있으면 당신의 실제 성과 역시도 줄어든다.

Appeal to Consequences: Arguing that a hypothesis must be true (or false) because the outcome is something you like (or dislike). The classic example is arguing that climate change isn’t real because combating climate change will hurt the economy.

결과에 의한 논증: 어떠한 가설의 결과가 당신의 마음에 드냐 안 드냐에 따라 가설의 참과 거짓을 주장하는 것. 전형적인 예로, 기후변화와 싸우는 것이 경제를 손상시키기 때문에 기후변화가 거짓이라고 주장하는 경우를 들 수 있다.

Plain Folks Fallacy: People of authority acquiring trust by presenting themselves as Average Joe’s, when in fact their authority proves they are different from everyone else.

평범한 사람들의 오류: 권위를 가진 자들은 자신들을 평범한 사람이라고 표현할 때 사람들의 신뢰를 얻을 수 있다. 권위를 가졌다는 것 자체로 이미 평범한 사람들과 다름에도 불구하고 말이다.

Behavioral Inevitability: “History never repeats itself; man always does.” – Voltaire

행동의 필연성: “역사는 절대 스스로 반복되지 않는다. 인간이 항상 그럴 뿐이다.” – 볼테르

Apophenia: A tendency to perceive correlations between unrelated things, because your mind can only deal with tiny sample sizes and assuming things are correlated creates easy/comforting explanations of how the world works.

아포페니아: 아무 관계없는 것들 사이에서 관련성을 찾으려는 성향. (Ex: 수염을 안 깎았더니 시험을 잘 봤다) 사람들은 현실의 많은 현상 중 작은 일부만을 감당할 수 있기 때문에 그러한 관련성을 만들어서 세상을 쉽고 편하게 이해하려 한다.

Self-Handicapping: Avoiding effort because you don’t want to deal with the emotional pain of that effort failing.

셀프 핸디캡: 노력하고 나서 실패했을 때의 심적 고통을 피하기 위해 아예 노력을 하지 않으려는 것.

Hanlon’s Razor: “Never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by stupidity.”

핸런의 면도날: “누군가의 멍청함으로 인해 설명되는 일을 악의의 탓으로 돌리지 마라.”

False Uniqueness Effect: Assuming your skills are unique when they’re not. Comes from conflating “I’m good at this” with “Others are bad at this.”

잘못된 독특성 효과: 당신이 가진 기술이 별 것 아님에도 독특하다고 가정하는 것. “다른 사람들은 이걸 못하던데” 와 “나는 이걸 잘하지”가 합쳐서 발생하는 인지 편향의 한 형태이다. (=내로남불)

Hard-Easy Effect: Hard tasks promote overconfidence because the rewards are high and fun to dream about; easy tasks promote underconfidence because they’re boring and easy to put off.

난이도 효과: 어려운 일은 과도한 자신감을 조장한다. 왜냐하면 어려운 만큼 보상이 높고 그에 대한 꿈을 꾸는 것이 재미있기 때문이다. 반면에 쉬운 일은 지루하고 미루기도 쉽기 때문에 과소평가된다.

Neglect of Probability: Arguing that Nate Silver was wrong when he said Hillary Clinton has a 70% chance of winning, and using Donald Trump’s victory as your proof. Good predictions are based on probabilities, but the assessment of predictions are always binary, right or wrong.

확률 무시: 미국 대선 때 힐러리가 이길 확률이 70%라고 말했던 네이트 실버(미국의 통계학자)의 사례를 들며 확률은 무시해도 된다는 주장. 하지만 좋은 예측은 확률을 기반으로 한다. 단지 그러한 예측에는 맞음 틀림 두 가지의 선택지밖에 없을 뿐.

Cobra Effect: Attempting to solve a problem makes that problem worse. Comes from an Indian story about a city infested with snakes offering a bounty for every dead cobra, which caused entrepreneurs to start breeding cobras for slaughter.

코브라 효과: 문제를 해결하려는 것이 오히려 문제를 더 악화시키는 현상. 도시에 뱀이 들끓자 죽은 뱀 한 마리 당 현상금을 줬는데 이를 악용해서 일부러 뱀을 번식시키고 죽이게 됐다는 인도의 이야기에서 유래되었다.

Braess’s Paradox: Adding more roads can make traffic worse because new shortcuts become popular and overcrowded.

브라에스의 역설: 새로운 도로를 추가하는 것이 교통체증을 오히려 악화시킬 수 있다는 내용. 왜냐하면 새로 생긴 지름길들이 인기 있어져서 오히려 그곳이 더 막히게 될 수도 있기 때문이다.

Non-Ergodic: When group probabilities don’t apply to singular events. If 100 people play Russian Roulette once, the odds of dying might be, say, 10%. But if one person plays Russian Roulette 100 times, the odds are dying are practically 100%.

비에르고딕: 그룹 확률이 단일 사건에 적용되지 않는 다는 원리. 예를 들어 100명이 1/10의 확률인 러시안 룰렛을 한 번 한다면, 죽을 확률은 10%일 것이다. 하지만 만약 한 명이 그 러시안 룰렛을 100번 한다면, 죽을 확률은 사실상 100%일 것이다.

Pollyanna Principle: It’s easier to remember happy memories than bad ones.

Pollyanna 원칙: 사람은 나쁜 추억보다 행복한 추억들을 기억하기 더 쉽다.

Declinism: Perpetually viewing society as in decline, because you’re afflicted by the Pollyanna Principle and you forget how much things sucked in the past.

Empathy Gap: Underestimating how you’ll behave when you’re “hot” (angry/aroused/rushed), caused by the inability to accurately foresee how your body’s physical response to situations (dopamine, adrenaline, etc.) will influence decision-making.

공감 간극: 당신이 열 받았을 때(흥분하거나 성급해 졌을 때) 어떻게 행동할지에 대해서 지나치게 낙관적으로 예측하는 것. 상황에 따른 당신의 신체적 반응을 예측하는 것이 어렵기 때문에 일어난다. (Ex: 상사한테 따질 때 침착하게 말해야지, 오늘 한 판만 이기고 자야지 등)

Abilene Paradox: A group decides to do something that no one in the group wants to do because everyone mistakenly assumes they’re the only ones who object to the idea and they don’t want to rock the boat by speaking up.

애벌린 패러독스: 한 집단 내의 모든 구성원이 자신의 의사에 반하는 방향으로 결정이 내려지는 데 반대하지 않고 오히려 동의하는 현상. 이는 모두들 반대하는 사람이 자기 하나만 있을 거라고 잘못 가정하고, 괜히 목소리를 높여 문제를 일으키는 것을 두려워하기 때문에 발생한다.

Collective Narcissism: Exaggerating the importance and influence of your social group (country, industry, company, department, etc.).

집단 나르시시즘: 당신이 속한 사회적 그룹(국가, 산업, 회사, 부서 등)의 영향력과 중요성의 과장하는 현상.

Moral Luck: Praising someone for a good deed they didn’t have full control over. “Avoid calling heroes those who had no other choice.” – Taleb.

Feedback Loops: Falling stock prices scare people, which cause them to sell, which makes prices fall, which scares more people, which causes more people to sell, and so on. Works both ways.

피드백 선/악순환: 주가 하락은 사람들을 겁먹게 하고, 주식들을 팔게 하고, 주가가 떨어지고, 이는 더 많은 사람들을 겁먹게 하고, 더 많은 주식을 팔게 만든다. 이는 반대 방향으로도 작용한다.

Hawthorne Effect: Being watched/studied changes how people behave, making it difficult to conduct social studies that accurately reflect the real world.

호손 효과: 관찰되거나 연구되고 있는 사람들은 (그 사실을 알고 있기 때문에) 행동이 부자연스럽게 변하게 되어, 현실 세계를 정확히 반영하려는 사회적 연구가 시행되기 어렵게 만든다.

Perfect Solution Fallacy: Comparing reality with an idealized alternative. Prevalent in any field governed by uncertainty.

완벽한 해결책 오류: 불완전한 현실을 인정하지 못하고 완벽한 이상을 추구하다 아무것도 이루지 못하는 것. 불확실한 환경이 존재하는 모든 분야에서 찾아볼 수 있다.

Weasel Words: Phrases that appear to have meaning but convey nothing tangible. “Growth was solid last quarter,” or “Many people believe.”

족제비 같은 말: 뭔가 그럴듯하게 들리지만 실제로는 아무 의미도 없는 말들. “지난 분기에 성장세가 확실했다” 혹은 “많은 사람들이 믿고 있다.” 등.

Hormesis: Something that hurts you in a high dose can be good for you in small doses. (Weight on your bones, drinking red wine, etc.)

호르미시스 효과: 많은 양을 투여했을 때 유해한 물질이라도 적은 양을 투여하면 좋은 효과를 볼 수도 있다. (당신의 뼈에 실리는 하중, 적포도주 마시기 등)

Backfiring Effect: A supercharged version of confirmation bias where being presented with evidence that goes against your beliefs makes you double down on your initial beliefs because you feel you’re being attacked.

역효과 현상: 확증편향의 강화버전으로 당신이 믿는 것과 반대되는 증거가 나왔을 때 (공격받는다고 느껴서) 당신의 믿음을 훨씬 더 굳건히 하려는 현상.

Reflexivity: When cause and effect are the same. People think Tesla will sell a lot of cars, so Tesla stock goes up, which lets Tesla raise a bunch of new capital, which helps Tesla sell a lot of cars.

Second Half of the Chessboard: Put one grain of rice on the first chessboard square, two on the next, four on the next, then eight, then sixteen, etc, doubling the amount of rice on each square. When you’ve covered half the chessboard’s squares you’re dealing with an amount of rice that can fit in your lap; in the second half you quickly get to a pile that will consume an entire city. That’s how compounding works: slowly, then ferociously.

체스판으로 설명하는 복리의 무서움: 체스판 한 칸에 곡물 한 알갱이, 다음에는 2 알갱이, 그 다음에는 4 알갱이, 그 다음에는 8 알갱이를 놓으며 두 배씩 양을 증가시켜 간다면, 처음에는 그 양이 얼마되지 않는 것처럼 보인다. 하지만 그렇게 체스판의 반을 넘어가게 되면 한 도시를 집어삼킬 만큼 곡물의 양이 불어난다. 이게 복리가 작동하는 방식이다. 느려보이지만, 결과는 파괴적이다.

Peter Principle: Good workers will continue to be promoted until they end up in a role they’re bad at.

피터의 법칙: 좋은 직원들은 그들이 못하는 직책에 올라갈 때까지 계속 승진한다(즉, 고위직에 올라간 직원들은 오히려 그 직책에서 무능한 상태가 된다).

Friendship Paradox: On average, people have fewer friends than their friends have. Occurs because people with an abnormally high number of friends are more likely to be one of your friends. It’s a fundamental part of social network dynamics and makes most people feel less popular than they are.

친구관계의 역설: 평균적으로, 사람들은 자신들의 친구들보다 더 적은 친구를 가지고 있다. 왜냐하면 비정상적으로 친구가 많은 사람은 당신의 친구일 확률도 높기 때문이다. (예를 들어 페이스북을 시작해서 누군가를 친구 추가하면, 그 누군가는 이미 여려 명의 친구를 가지고 있을 것이다.) 이것은 소셜 네트워크 역학의 근본적인 부분이며 대부분의 사람들이 자신들이 덜 인기가 있다고 느끼게 만든다.

Hedonic Treadmill: Expectations rise with results, so nothing feels as good as you’d imagine for as long as you’d expect.

쾌락 적응: 당신의 기대치는 결과가 올라가면 따라서 올라가게 된다. 즉, 당신이 상상했던 것만큼 좋게 느껴지는 것은 없다.

Positive Illusions: Excessively rosy views about the decisions you’ve made to maintain self-esteem in a world where everyone makes bad decisions all the time.

긍정적 환상: 모두가 잘못된 결정을 하는 세상에서 자존감을 유지하기 위해 자신이 내린 결정들을 지나치게 낙관적으로 보는 현상.

Ironic Process Theory: Going out of your way to suppress thoughts makes those thoughts more prominent in your mind.

강박사고 억제의 역설적 효과: 어떤 생각을 억누르기 위해 애를 쓰면 반대로 더 생각나게 된다.

Clustering Illusions: Falsely assuming that the inevitable bunching of random results in a large sample indicates a trend.

군집 환상: 필연적으로 나타나는 (소수의) 무작위 결과 값을 보고 (패턴이 있다고) 착각하여 실제 트렌드를 잘못 예상하는 현상.

Foundational Species: A single thing that plays an outsized role in supporting an ecosystem, whose loss would pull down many others with it. In nature: kelp, algae, and coral. In business: The Federal Reserve and Amazon.

기초 종: 생태계에서 아주 큰 역할을 하여 생태계를 떠받치는 역할을 하는 단일 종. 이러한 종에 손실이 발생하면 이와 관련된 다른 종들도 피해를 입는다. (자연: 다시마, 해조류, 산호) (비즈니스: 연방준비제도이사회, 아마존)

Bizarreness Effect: Crazy things are easier to remember than common things, providing a distorted sense of “normal.”

특이함 효과: 미쳐 보이는 건 정상적인 것보다 더 기억하기 쉽고, 그로 인해 ‘정상적’이라는 감각을 왜곡시킨다.

Nonlinearity: Outputs aren’t always proportional to inputs, so the world is a barrage of massive wins and horrible losses that surprise people.

비선형성: 산출물이 항상 투입량에 비례하지 않기 때문에, 세상에는 사람들을 놀라게 하는 엄청난 승리와 패배가 계속해서 나타난다.

Moderating Relationship: The correlation between two variables depends on a third, seemingly unrelated variable. The quality of a marriage may be dependent on a spouse’s work project that’s causing stress.

관계 조정: 어떤 두 변수의 연관성은 겉으로는 관계없어 보이는 세 번째 변수에 달려 있는 경우가 있다. 예를 들어 결혼 생활의 질은 (생뚱맞게도) 스트레스를 유발하는 배우자의 업무 프로젝트에 달려 있을 수도 있다.

Denomination Effect: One hundred $1 bills feels like less money than one $100 bill. Also explains stock splits – buying 10 shares for $10 each feels cheaper than one share for $100.

액면가 효과: 1달러짜리 100장은 100달러짜리 한 장 보다 더 적게 느껴진다. 주식 역시 마찬가지다. 10달러 주식을 10개 사는 것은 100달러 주식을 한 개 사는 것보다 싸게 느껴진다.

Woozle Effect: “A reliable way to make people believe in falsehoods is frequent repetition, because familiarity is not easily distinguished from truth.” - Daniel Kahneman.

우즐 효과: “사람들에게 거짓을 믿게 하는 효과적인 방법은 그 거짓을 계속 반복하는 것이다. 왜냐하면 그러한 익숙함은 진실과 구별하기 쉽지 않기 때문이다.” – 대니얼 카너먼(노벨경제학상 수상 심리학자)

Google Scholar Effect: Scientific research depends on citing other research, and the research that gets cited the most is whatever shows up in the top results of Google Scholar searches, regardless of its contribution to the field.

구글 스콜라 효과: 과학적 연구는 다른 연구를 얼마나 인용하는지에 달려있는데, 가장 많이 인용된 연구는 그것이 무엇이든 구글 스콜라 검색 결과의 상위권에 올라간다. 그 연구가 해당 분야에 얼마나 기여했는지에 관계없이 말이다.

Inversion: Avoiding problems can be more important than scoring wins.

반전: 때로는 문제를 피하는 것이 해결하는 것보다 더 중요할 때가 있다.

Gambler’s Ruin: Has many meanings, the most important of which is that playing a negative-probability game persistently enough guarantees going broke.

도박꾼의 파멸: 많은 뜻을 가지고 있지만, 그 중 가장 중요한 것은 안 좋은 확률의 게임을 지속적으로 하면 반드시 파산한다는 것이다.

Principle of Least Effort: When seeking information, effort declines as soon as the minimum acceptable result is reached.

최소 노력의 원리: 정보를 찾을 때, 최소한 받아들일 수 있을 수준의 정보를 찾자 마자 노력의 양은 줄어든다.

Dunning-Kruger Effect: Knowing the limits of your intelligence requires a certain level of intelligence, so some people are too stupid to know how stupid they are.

더닝 크루거 효과: 자기자신의 지능의 한계를 알려면 어느 정도의 지능이 요구되는데, 어떤 사람들은 너무 멍청하기 때문에 자신들이 얼마나 멍청한 지도 모른다.

Knightian Uncertainty: Risk that can’t be measured; admitting that you don’t know what you don’t know.

Knightian 불확실성: 어떤 위험은 측정할 수 없다. 당신이 모르는 것에 대해선 모른다고 인정할 줄 알아야 한다.

Aumann’s Agreement Theorem: If you understand your opponent’s beliefs you cannot agree to disagree. If you agree to disagree it’s because one side doesn’t understand the other side’s view.

오만의 동의 이론: 상대방의 신념을 이해할 수 있게 된다면 그들에게 동의할 수밖에 없게 된다는 이론. 만약 당신이 다른 사람의 견해에 동의할 수 없다면 그것은 당신이 그들을 이해하지 못했기 때문이다.

Focusing Effect: Overemphasizing factors that seem important but exist as part of a complex system. People from the Midwest assume Californians are happier because the weather is better, but they’re not because Californians also deal with traffic, bad bosses, unhappy marriages, etc, which more than offset the happiness boost from sunny skies.

집중 효과: 복잡한 시스템의 일부에 불과한 부분을 과도하게 중요하다고 여기는 경향. 예를 들어 미국 중서부의 사람들은 날씨가 좋은 곳에 있는 캘리포니아 사람들이 더 행복하다고 생각한다. 하지만 실제 그들은 교통 체증, 상사와의 갈등, 불행한 결혼 등으로 인해 그다지 행복하지 않다. 맑은 하늘만으로 이러한 불행들을 상쇄하기엔 턱없이 부족하기 때문이다.

The Middle Ground Fallacy: Falsely assuming that splitting the difference between two polar opposite views is a healthy compromise. If one person says vaccines cause autism and another person says they don’t, it’s not right to compromise and say vaccines sometimes cause autism.

중도의 오류: 극과 극의 대립되는 두 견해의 중간 지점이 합리적이라고 잘못 가정하는 것. 예를 들어 어떤 한 사람이 백신이 자폐증을 유발한다고 하고 다른 사람이 그렇지 않다고 할 때, 양쪽 주장을 타협하여 ‘백신은 가끔 자폐증을 유발한다.’ 라고 말하는 것은 옳지 않다.

Rebound Effect: New symptoms, or supercharged old symptoms, emerge when medicine or other protections are withdrawn.

Ostrich Effect: Avoiding negative information that might challenge views that you desperately want to be right.

타조 효과: 사람은 자신들이 믿고 싶은 주장에 반대되는 정보를 피하려는 습성이 있다.

Founder’s Syndrome: When a CEO is so emotionally invested in a company that they can’t effectively delegate decisions.

설립자 증후군: CEO가 너무 회사에 감정적으로 얽매여 있어서 효율적으로 회사의 결정을 대리할 수 없을 때.

In-Group Favoritism: Giving preference to people from your social group regardless of their objective qualifications.

그룹 내 편향성: 사람들은 누군가가 객관적인 자격을 갖췄나 보다는 자신들의 사회적 그룹 내에 있는 사람들에게 더 잘해주려고 한다.

Bounded Rationality: People can’t be fully rational because your brain is a hormone machine, not an Excel spreadsheet.

제한적 합리성: 사람들은 완전하게 이성적일 수는 없다. 왜냐하면 당신의 뇌는 기본적으로 호르몬이 흐르는 기계이지 엑셀 스프레드시트가 아니기 때문이다.

Luxury Paradox: The more expensive something is the less likely you are to use it, so the relationship between price and utility is an inverted U. Ferraris sit in garages; Hondas get driven.

사치의 역설: 더 비싼 것일수록 사람들은 더 적게 사용한다. 따라서 가격과 효용성의 관계는 거꾸로 된 U자 형태의 그래프가 된다. 페라리는 주로 차고에 있지만, 혼다는 드라이브하는데 쓰인다.

Meat Paradox: Dogs are family, pigs are food. Some animals classified as food are wrongly perceived to have lower intelligence than those classified as pets. An example of morality depending on utility.

고기의 역설: ‘개는 가족, 돼지는 음식.’ 이처럼 음식으로 취급 받는 동물들은 애완동물로 분류 되는 동물들보다 지능이 더 낮다고 잘못 인식되곤 한다. 이는 도덕적 구분이 대상의 효용성에 따라 결정되는 좋은 예이다.

Fluency Heuristic: Ideas that can be explained simply are more likely to be believed than those that are complex, even if the simple-sounding ideas are nonsense. It occurs because ideas that are easy to grasp are hard to distinguish from ideas you’re familiar with.

유창 휴리스틱: 단순하게 설명할 수 있는 아이디어는 비록 말도 안되는 소리처럼 들리더라도, 복잡한 아이디어보단 더 신뢰받을 수 있다. 왜냐하면 이해하기 쉬운 아이디어와 당신이 평소 친숙하게 느끼는 아이디어는 구별하기 어렵기 때문이다.

Historical Wisdom: “The dead outnumber the living 14 to 1, and we ignore the accumulated experience of such a huge majority of mankind at our peril.” – Niall Ferguson

역사의 지혜: “지금까지 죽은 사람들의 수는 살아있는 사람보다 14배나 많다. 우리는 위기에 처했음에도 과거부터 인류 역사에 축적된 그 엄청난 경험들을 무시하고 있다.” – 니얼 퍼거슨

Fact-Check Scarcity Principle: This article is called 100 Little Ideas but there are fewer than 100 ideas. 99% of readers won’t notice because they’re not checking, and most of those who notice won’t say anything. Don’t believe everything you read.

팩트-체크 희소성의 원칙: 지금 이 기사의 제목은 ‘100개의 작은 아이디어들’이지만 사실 실제론 100개가 되지 않는다. 99%의 독자들은 이를 체크하지 않기 때문에 모르고, 눈치챈 사람들조차 대부분은 아무 말도 하지 않는다. 당신이 읽는 모든 것이 진짜라고 생각하지 마라.

Emotional Contagion: One person’s emotions trigger the same emotions in other people, because evolution has selected for empathizing with those in your social group whose actions you rely on.

감정적 전염: 한 사람의 감정이 다른 사람에게도 비슷한 감정을 불러일으키는 경우가 있는데, 이는 인간은 자신이 의존하고 있는 사회적 그룹과 공감하며 살게끔 진화하였기 때문이다.

Tribal Affiliation: Beliefs can be swayed by identity and a desire to fit in over rational analysis. There is little correlation between climate change denial and scientific literacy. But there is a strong correlation between climate change denial and political affiliation.

부족적 소속감: 신념은 이성적인 분석보다는 정체성과 어울리고 싶은 욕구에 의해 좌우된다. 기후 변화 부정과 과학적 소양 사이에는 서로 별다른 관련성이 없지만, 기후 변화 부정과 정치적 성향 사이에는 밀접한 관련성이 있다.

Emotional Competence: The ability to recognize others’ emotions and respond to them productively. Harder and rarer than it sounds.

정서적 능력: 다른 사람의 감정을 파악해서 그에 맞게 생산적으로 대응할 수 있는 능력. 생각보다 어렵고 귀한 능력이다.

-----

원문 : https://www.collaborativefund.com/blog/100-little-ideas/